The Involuntary Doom Element

Yet another tragic and cautionary tale from the world of sports.

I got a terrible text from an old friend. A kid we grew up with, a renowned MMA fighter, was arrested for murder. We weren't surprised, and I don't want to get into the details.

My prayers go out to the victim and her family. If he did what they say, and it looks that way, he deserves what he gets. "Buy the ticket, take the ride." If it were my daughter under some blanket, I'd be baying for blood…

This vile act is the coda to a twisted Faustian cantata.

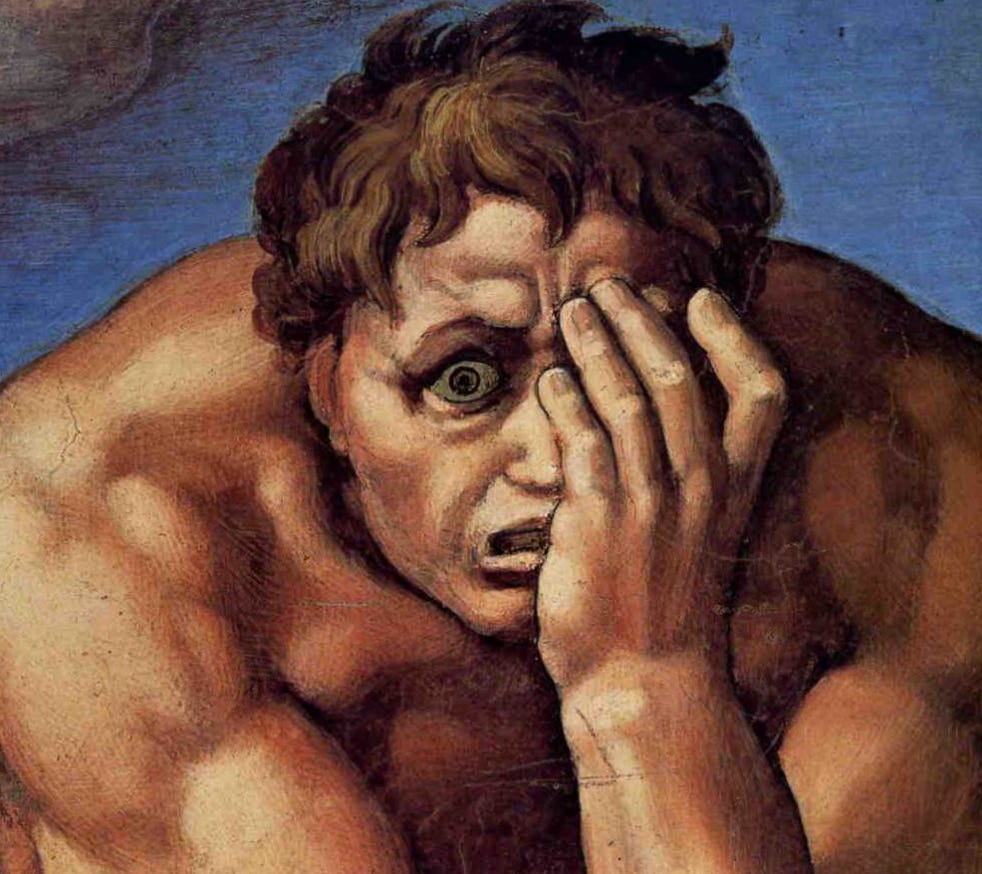

These photos kept me up all night as old memories flooded in.

The kid we knew, bearded now, sits in delirium on a cheap metal chair. A dim light illuminates the tropical night as a Mexican cop glowers at another drunk gringo. Four decades of vice converged into this definitive dissipation. A door is chocked. Inside, on the bed, a woman lies dead under a blanket. He told them he put it over her for warmth as he set out for more beer and cigarettes.

If you don't believe in hell, look; it's right there, just inside Unit 3 of Jardín San Pancho B&B. It envelops the kid we used to know; it swirls around the defeated tilt of his head. Those who've seen temporal hell recognize the familiar signs and body language. How ordinary it all is; the weight of the dank air, the empty beer cans, fast-food wrappers, melting ice in sweating glasses, a late-night TV commercial on mute, a body under a thin sheet, gone like a train.

Childhood memories belong to you in the strangest ways. I carry mine like a broken toy inside an old Buster Brown shoebox.

When the man in the metal chair was a boy, I recall him acting suspicious, self-conscious, savage, unmanageable, and violent. He was also vulnerable, curious, intelligent, and seemed very lonely, though not alone.

One afternoon, maybe after one of the frequent tackle football games we played at the Hawthorn "U," we walked home together. We were tough guys, so we needed to know who was the real predator and who was just prey. We decided to fight it out, alone, in the middle of a vast field that separated our elementary school from the junior high. There was no anger between us; we just wanted to know who was who. I was bigger and older and had a stable reputation; he was the wildcard. We began. Instantly, I felt his rage. He had an energy I did not possess. The scrap was a draw, but I knew deep down I wanted no part of this kid. We had taken our test and never mentioned it as we continued our walk home. Deep down, I knew I had lost something.

Home brought him no satisfaction. His house seemed plain, lonely, austere, cold, without love; like something you rent. Not run down, just bland and banal. So banal that he may have felt the need to devise a brighter life, more alive and in Technicolor with big opening credits.

Seven or so years later, at Mulcahy's (of course), we had words about something stupid; I can't remember what. He wasn't an undersized fifth grader anymore, and I wasn't so confident. He bore a well-earned sinister posture. I tried to reason with him. As Ace of Base pounded in the background, my placation dropped into his dead eyes. I secretly palmed a Bud bottle under the bar, preparing for a defensive glassing. I must have said something to soothe him because, miraculously, tensions lifted. I made up an excuse to leave and said goodbye. That exit might have been my most intelligent up to then. I wasn't dumb enough to have another go.

That night might have been the last time we talked.

It all seems so abnormal now, and unfortunate. All that tiresome Long Island meathead posturing. All that wasted time.

So there he is on a balmy winter night, not far from the banks of the Bay of Banderas, alone and a long way from home. He'd run as far from his external and unavoidable self as he could, but he was still in the demons' shadow, and the nightmare just bottomed out.

We all possess an involuntary doom element. That temptress which goads us and palpitates and plots to divide us from our default goodness. Some of us are aware of it, most deny it, the lucky ones never encounter it.

The kid knew his doom element like a mother knows her child. He raised it properly and turned it into a sword, smelting and forging it into carbon-laced steel that was rigid, flexible, and able to withstand the rigors of battle. He then wielded it like a clumsy child and used it to gain third-rate fame and a few big fleeting paydays.

The doom element became his 'heart' and 'soul,' his entire identity. It was who he was. It got him fame, girls, booze, drugs, and money. Now they want him to turn his back on it, deny it. Fuck that! He was no traitor, no sell-out. He'd stand by that fuckin' doom element to the bitter end. And this was his ruinous conceit.

Let it be said here and now: This vain delusional devotion to the doom element is nothing more than a vile allegiance to a perverted, burned-out pedophile. A fruitless debauch into madness.

If you see it - run.

The eminent Soviet dissident and novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) would instantly recognize the kid's concession to the doom element. Solzhenitsyn understood that evil passed through every human heart. He writes in The Gulag Archipelago: "This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained."

So was there good inside him? Of course. I saw it back then. I knew the people around him when he was young. His coaches and teachers, and friends. He was told what the right things were. How to be a gentleman. He knew right from wrong. Good from evil. So if we who knew him way back when weaved our unreliable and refracted remembrances altogether, could we say with certainty that this monstrous act could have been prevented?

Who knows?

I wonder if he truly recognized and understood the violent potential the doom element represented. Maybe he did and just forgot to chain it to the radiator.

For most, our evil impulses are quelled by maturity, self-knowledge, marriage, children, and a steady job. For him, it raged inside a motel room in Mexico.

On the morning of June 18th, 1994, around the time I’d last seen the kid at 'Muls,' I must have had a dreadful night; stitches, blood, etc. The details are not important. Let’s just say I was a mess.

The Knicks and Rangers were on a magical playoff run, and O.J. Simpson had just surrendered on Bundy Drive in Brentwood a few hours back, PT.

My head pounded on that bright late spring morning.

The Juice story was a big deal. It is hard to explain to young people just how big. It swallowed everything. Even my father, an old-school retired NYPD cop, was sucked into its pathos.

We sat across from each other on lawn chairs. He was nearly shaking, looking at me, his bloody wretched son. All he said was this: "There's a guy sitting in a jail cell right now wondering what the hell he just did. His life is over. He threw it all away. And for what?"

I’d swear he was almost crying. A very rare sight. Then I realized why. He was comparing me to a murderer. Not that he thought I was capable of murder, but that my reckless and wild ways would put me into a very bad place. The way he looked at me was terrifying. Like the way you might look at a prisoner before he’s executed. He understood the quick work of senseless acts of violence and how the doom element can destroy everything instantly.

My father's heartbreaking comparison of me, his son, to a killer (yes, O.J. did it) shook me. It rattled my already delicate confidence. I felt that if my father couldn't trust me, how could I trust myself? I'm sure it hurt our relationship, but I think it really slowed me down. He forced my awareness of my involuntary doom element. As a father of three boys, I now know how hard that must have been, but it might have saved my life. I learned over the years how to chain that beast to the radiator.

I wonder if my old friend’s father ever gave the same heads-up. Maybe he did? Perhaps he heard the warnings so much he thought he'd never be able to trust himself, so why fucking bother. But let us all remember this: "Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him." — Fyodor Dostoevsky.